The Enigmatic Story of the Mary Celeste

Image credit: PHOTOCREO Michal Bednarek/Shutterstock.com

There have been many maritime mysteries down the years but few have been as enduring or remained as prominent, as that of the Mary Celeste. The shroud of myth and legend surrounding the vessel is now very much part of maritime folklore. Such is ship’s infamy that any unexplained disappearance, in any circumstance, is often referred to ”as being like the Mary Celeste”. Not unsurprisingly, many falsehoods have been told about the notorious ship since it was found abandoned in 1872. Thus, it has proved extremely challenging for historical researchers to determine fact from fiction.

Over the years, dozens of scenarios have been propositioned as the solution to the Mary Celeste mystery. These have ranged from the over-simple to the ridiculous. No one knows what took place aboard the distressed merchant ship almost 150 years ago. In all probability – no one ever will! However, just what is the backstory to one of history’s most renowned ships?

The Mary Celeste was an American 103-foot, 282-ton brigantine. It was found abandoned at sea on 4 December 1872, some 590 miles west of Gibraltar. It was found by the Canadian ‘Dei Gratia’, a ship that the Mary Celeste had been berthed within New York while taking on cargo during the previous month. On November 7th, Captain Briggs of the Mary Celeste had sailed for Genoa. Around 15 November, Captain Moorhouse of the Dei Gratia set sail for Gibraltar.

The Derelict

On the 4th December, Captain Moorhouse sighted the Mary Celeste with its sails set, sailing with the wind, but in an erratic manner. Feeling something was sadly amiss, he sent a boarding party to investigate. They found the ship completely deserted. Captain Briggs, his wife, his daughter, and its eight crew members were all missing. According to the most reliable reports, it appeared that the ship’s only lifeboat had been launched. However, other accounts have put the lifeboat as still being on board.

Descriptions of the Mary Celeste’s condition, vary quite considerably. However, the general consensus seems to be that the vessel was in relatively good order. Some accounts of the story suggest a meal was just about to be served, while others say it was still cooking on the stove. All dishes, cutlery, and cooking utensils were properly stored, according to some. A different version says bacon, eggs, bread, and butter, and coffee had just been served and was still on the table.

The Captain’s personal effects were all still on board. Children’s toys, that looked as though they had been recently played with, were found on his bed. The ship’s cargo of 1,701 barrels of industrial alcohol was reported as being perfectly intact. However, water around 3 ft deep was found in the hold. The ship’s papers and navigation instruments were all missing, with the exception of the Captain’s Log. However, a six-month supply of food and water was still on board.

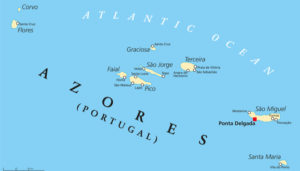

The Captain’s sword was found hanging from a bulkhead. Though, it was said to be under his bed, according to a different report. In alternative versions of events, the sword was either rusty or covered with blood. There was also blood, or possibly wine stains, on some of the woodwork and sails. Other accounts do not mention any blood at all. The last entry in the ship’s log was on 24 November. It documented the ship as being 100 miles west of the Azores. Found eleven days later, it had by that time drifted 500 miles east of that position.

The Mary Celeste was found approximately 400 miles East of the Azores. Image credit: Peter Hermes Furian/Shutterstock.com

The Gibraltar Hearings

The crew from the Dei Gratia sailed the derelict to Gibraltar, some 600 nautical miles (1100 km) away. They arrived at the port on the morning of the 13th of December. The ship was immediately impounded by the Admiralty. This signalled the start of a lengthy and controversial inquiry. Many versions of what had happened were told, retold, changed, and embellished. For a time, Captain Moorhouse was accused of piracy, said to have seized the ship for its salvage value, and killed the crew. It was even rumoured that he had planted crew on board the Mary Celeste in New York. They took over the ship, threw everybody else overboard, and then waited for the Dei Gratia to catch up.

A theory was even put forward by William A. Richard, then Secretary of the Treasury of the United States. He wrote an open letter to the New York Times, which appeared on the front page of the 25 March 1873 edition. He hypothesised that the intoxicated crew murdered the captain and his family in a drunken frenzy. They had then abandoned ship by lifeboat and possibly perished at sea. However, he supposed it more likely they had been picked up by another vessel and had been landed somewhere in America or the West Indies.

One much simpler account was that the ship must have been caught in a storm. When it seemed the ship was about to sink, the crew had abandoned it for the lifeboat. Another theory was that vapour resembling smoke had poured from the hold. This had led Captain Briggs to think the vessel was about to catch fire or blow up. Thus, he then gave the order for the crew to launch the lifeboat, and subsequently, everyone abandoned the ship. The crew had attached a line to the ship as a fallback position but the rope somehow became severed. This had left the Mary Celeste to drift off on her own.

Another explanation of the crew’s disappearance at the time mooted the possible presence of a displaced iceberg. However, hydrographical evidence suggests that an iceberg drifting so far south was highly improbable. Another theory suggested the Mary Celeste became becalmed and began drifting towards the Dollabarat reef, off the Island of Santa Maria Island. The theory supposes that Briggs feared the vessel would run aground and thus launched the ship’s yawl. The wind then picked up and blew Mary Celeste away from the reef. However, the rising seas swamped and sank the yawl.

In the end, nothing could be proved. This lead to Captain Moorhouse and his crew eventually being awarded a small salvage fee.

The official hearing into the Mary Celeste was held in Gibraltar. Image credit: Dziewul/Shutterstock.com

Final Years of the Mary Celeste

The Mary Celeste arrived back in New York on the 19th of September 1873. The Gibraltar hearings, with its many sensational tales of woe, including murder, had not unsurprisingly made her an unpopular ship. It was recorded that the Mary Celeste “… rotted on wharves where nobody wanted her.” In February 1874, the ship was sold to a partnership of New York businessmen at a considerable loss.

Under its new ownership, the Mary Celeste mainly sailed between the West Indies and the Indian Ocean. However, it reportedly lost money on a regular basis. In February 1879, she docked at the island of St. Helena, where medical assistance was sought for the captain. Edgar Tuthill, died unexpectedly on the island, becoming the third ship’s captain to die prematurely. The new incident did little to discourage the idea that the ship was cursed.

In February 1880, the Mary Celeste was sold to new owners in Boston. In November 1884, a recently appointed new captain, Gilman C. Parker, conspired with a group of Boston shippers in an insurance scam. The ploy involved loading up the Mary Celeste with a largely worthless cargo and insuring it for many times more than its true value.

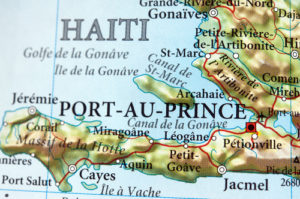

On January 3, 1885, the ship was deliberately run aground on a coral reef at the approach to the harbour of Port-au-Prince, Haiti. The ship was wrecked beyond repair but the scam was rumbled following the subsequent investigation. Parker was lucky to escape jail but died in poverty just 3 months later. One of his co-accused went mad, while another committed suicide.

In 1885, the Mary Celeste was deliberately run aground off the coast of Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Image credit: Juan Camilo Bernal/ Shutterstock.com

Further Speculation and Supposition

A Work of Fiction

One of the most influential retellings of the Mary Celeste incident was a short story, published in the January 1884 edition of the Cornhill Magazine. The story was written by a little-known author, Arthur Conan Doyle, who was then a 25-year-old ship’s surgeon. Doyle’s feature was titled ‘J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement’. It borrows heavily on the Mary Celeste events but was intended as a work of fiction. He renamed the ship, Marie Celeste, the captain’s name was J. W. Tibbs. The ship’s intended voyage was from Boston to Lisbon, and the event took place in 1873.

In Doyle’s story, unlike the real event, the vessel carried passengers. Among them was the fictional Jephson, and the terrorist, Septimus Goring, a hater of the Caucasian race. In Doyle’s narrative, Goring coerced members of the crew to murder Captain Tibbs. He then sailed the ship to the shores of Western Africa. Once ashore, the ship’s company were all murdered. Only Jephson was spared because of the cordial relationship he had struck up with Goring during the voyage.

Doyle had not expected his story to cause any kind of hue and cry. However, even the serving US consul in Gibraltar, Horatio J. Sprague, intrigued by the story, asked if any part of it might be true. Much of Doyle’s fictional Marie Celeste story was often later retold as the actual events that had taken place aboard the Mary Celeste.

More Theories

Following, Doyle’s work of fiction, other theories on the disappearance of the crew of the Mary Celeste became increasingly bizarre. One suggested that food poisoning had caused those aboard to suffer vivid hallucinations and that they all ended up jumping into the sea. Another was that the ship’s cook had poisoned everyone abroad. He then threw the bodies overboard and then jumped into the sea himself.

‘Barratry’, deliberate fraud by the ship’s owners, was voiced as another possibility. It supposed both the ship crew and that of the Dei Gratia were complicit in the deception. Another story had the ship’s owners in cahoots with the crew who had been instructed to murder Captain Briggs and his family. The plan had involved the crew jumping overboard and the ship being smashed on rocks near the Azores. However, the plan backfired when a sudden change in wind direction had blown the unmanned ship to safety. It was then the crew who had perished instead.

Another obscure theory was that the sudden disturbance caused by a nearby submarine had panicked the crew into abandoning the ship. The ship had then become grounded on a moving sandbank. Thinking the situation hopeless, the crew had then launched the ship’s yawl. While the crew perished at sea, the Mary Celeste had eventually become free of the island, setting sail unmanned. An even more bizarre story was that everyone had been plucked from the ship’s deck by a giant octopus.

A Swimming Contest, Treasure and Murder

In 1913, The Strand Magazine printed an alleged survivor’s account by Abel Fosdyk, supposedly the Mary Celeste’s steward. In his version, all onboard apart from himself had gathered on a temporary platform. It had been rigged up so everyone could get a good view of a swimming contest between the ship’s captain and the first mate. A freak wave had hit the ship, the platform collapsed, and everyone ended up in the sea. According to Fosdyk, they all then met their deaths after being eaten by sharks.

In 1924, the Daily Express printed a story that had supposedly been sourced from the former ship’s bosun. In this version, the ship had encountered another derelict vessel that had treasure on board. Thus, the crew decided to abandon the Mary Celeste to man the new ship. They sailed the ship on to Spain where they split the proceeds, and all lived happily ever after. However, the fantastic tale had one basic flaw. The Mary Celeste never had a ship’s bosun listed as a crew member.

In July 1926, yet another story was written about the ill-fated ship. Irish writer, Laurence J. Keating’s story was printed and given much credence by the New York Herald. The tale, as recounted by the previously unknown John Pemberton, told a complex tale of murder, madness, and collusion with the Dei Gratia.

Recent Investigation

In 2006, an experiment was carried out for the UK’s Channel 5 television by Andrea Sella of University College, London. The results of the experiment helped to revive the “explosion” theory. A model was built of the Mary Celeste’s hold, with paper cartons representing the barrels. Using butane gas, a trial explosion caused a considerable blast and ball of flame. However, contrary to expectations, there was no fire damage within the replica hold. “What we created was a pressure-wave type of explosion. There was a spectacular wave of flame but, behind it, was relatively cool air. No soot was left behind and there was no burning or scorching.”

Alas, that’s the enigmatic story of the Mary Celeste! A tale that continues to intrigue as much today as it has at any time since that fateful event of some 150 years ago.

Header image credit: Yarikart/Shutterstock.com