What is a Highwayman?

Highwaymen as they were dubbed in Britain, and elsewhere known as land-pirates, mail-coach robbers, stagecoach robbers, road agents, or bushrangers, and in Ireland, sometimes as Rapparees, were outlaws who plied their trade along the travelled highways of the world. In Britain and Ireland, they were active for around 200 years, between the early 17th and 19th centuries.

Claude Duvall in Brief

Claude Duvall (also named Duval and Du Vall) was a 17th-century highwayman of French origin who plied his trade around the roads of southeast England. According to popular legend he was a man that detested violence who showed only the greatest of courtesy towards his victims.

Dubbed the ‘Gallant Highwayman’, Duvall, more than any of his contemporaries was responsible for spawning the romanticised notion of the gentlemanly highwayman. The fact that he was also known to be very much a ladies man only added to his mystique. Duvall’s reputation has been upheld in paintings, poems, books, and even a couple of comic operas, with most of the works emanating from the 19th century.

How much do you know of Claude Duvall? Here’s a brief biography of the original dandy highwayman Claude Duvall:

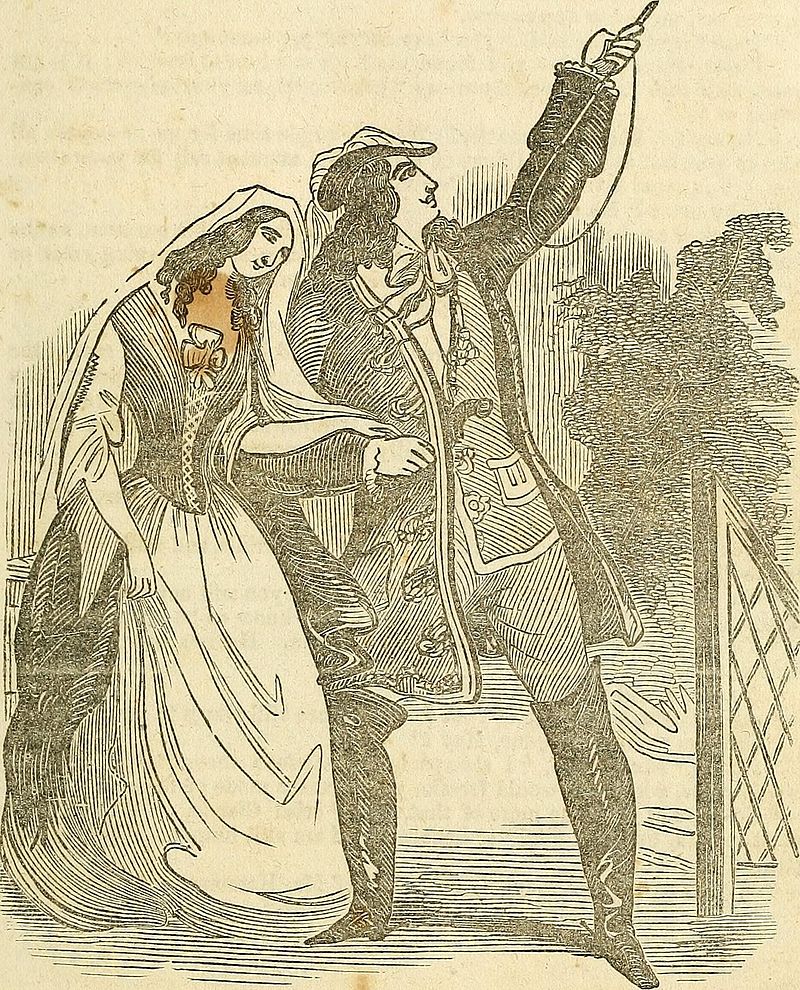

Image Credit: Internet Archive Book Images

Early Life

Claude Duvall was born in Domfront, Orne, Normandy in 1643, to parents’ Pierre, a miller and Marguerite, a tailor’s daughter. Reputedly, his family were of former nobility that had been stripped of title and land, but this is often disputed. What is known though is that by the age of 14, Claude was working in Rouen as a domestic servant. There he met and introduced himself to a group of English Lords who were on vacation and heading to Paris. They ended up hiring Duvall as a guide and general dogsbody for the rest of their trip – the young Claude had found his niche.

A Move to England

In 1660, just as England saw the restoration of the monarchy with Charles II coming to the throne, Duvall managed to secure employment as a footman at the home of Charles Stewart, 3rd Duke of Richmond. Things went well for Claude for a while as he settled in well to life in his newly adopted country. However, that was until there was a rumour circulating that Duvall had become more than friendly with the Duke’s fiancee. The penniless Claude left his employment under a cloud so with his future work prospects looking pretty bleak, he decided to join the ranks of the rouges of the road and become highwaymen.

The Notorious Claude Duvall

Duvall soon became notorious throughout the country, with his fame resting as much on his charm, exquisite manners and the chivalry shown towards his victims, rather than just the nature of his daring robberies. His main prey became stagecoaches on the roads into London, especially around the Holloway, Highgate and Islington areas.

Amongst his many exploits, on one famed occasion, he stopped a coach on Hounslow Heath (or Bagshot Heath) in which a gentleman and his wife were found to be travelling with £400 in cash. During the robbery, the lady began to play the flageolet (small flute) she had brought along for entertainment during her journey. Almost immediately she was asked by Duval to dance with him at the roadside. The man’s wife agreed to his request and solemnly executed a coranto (16th-century court dance), while her fuming husband looked on. The story goes that Duvall was then asked by the woman to pay for his entertainment, whereby he proceed to take only £100 before allowing the coach to get on its way. The event was immortalised by William Powell Frith in his famed 1860 painting ‘Claude Duval’ (see below).

William Firth’s painting ‘Claude Duval’. Image credit to Manchester Arts Council

A Fatal Mistake

However, not all and sundry were enraptured by the Duvall tales of gallantry. The very mention of his name struck fear in the hearts of many travellers, which ultimately led to large rewards being offered for his capture. Duvall sensed the authorities were hot on his trail, so felt it was a good time to head back to his homeland of France to lay low for a while. However, after only a few months he made the fatal decision to return to his old stomping ground around southeast England. Shortly after returning, he was arrested, while drunk, at the ‘Hole-in-the-Wall’ in Chandos Street, Covent Garden, London.

Trial and Execution

On 17th January 1670, he was put on trial at the Old Bailey, found guilty on six specimen charges of robbery and subsequently condemned to death. It’s said that a number of influential women tried to mediate with the King on Duval’s behalf, but he had been expressly excluded from any chance of a pardon. Thus, on the Friday following 21st January 1670, he was executed at Tyburn in Middlesex, reportedly to the sound of a host of weeping women and girls.

His body was cut down and laid in state at the Tangier Tavern, St. Giles’ where it was visited by large crowds of people from all backgrounds. It is thought Duvall was buried under the centre aisle of the church of St Paul’s in Covent Garden. An epitaph at the church to Claude Duvall reads:

Here lies Du Vall: Reader, if male thou art,

Look to thy purse; if female, to thy heart.

Much havoc has he made of both; for all.

Men he made to stand, and women he made to fall.

The second Conqueror of the Norman race,

Knights to his arm did yield, and ladies to his face.

Old Tyburn’s glory; England’s illustrious Thief,

Du Vall, the ladies’ joy; Du Vall, the ladies’ grief.

The Legend of Claude Duvall

In Literature

Since his death, Claude Duvall’s name and character have featured in both a number of novels and historical books. Duvall was famously included in William Harrison Ainsworth’s popular early 19th century novels; Rookwood and Talbot Harland, which helped to cement his iconic image as the gentleman highwayman. He also featured heavily in the Penny Bloods (later Penny Dreadfuls), which were early fictionalised adventure comics first published in the 1830s. In recent times, such as in Mary Hooper’s 2005 book ‘The Remarkable Life and Times of Eliza Rose’, Duvall is said to be a friend of Nell Gwyn and is even credited with saving the life of King Charles II. Michelle Lowe’s novel, Cherished Thief, published in 2012, was an account of Claude Duvall’s entire life story.

Stage and Screen

The character of Claude Duvall was written into John Gay’s epic ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ of 1728. In 1920, the Opera began a revival run of 1,463 performances at the Lyric Theatre in Hammersmith, London. It was one of the longest runs ever for a piece of musical theatre at that time. In 1881, a comic opera called ‘Claude Duval’ was written by Edward Solomon and Henry Pottinger Stephens, which went on to enjoy great success in both Britain and America.

In 1924, the British silent adventure film ‘Claude Duval’ directed by George A. Cooper and starring Nigel Barrie was released, proving popular with cinema-goers.

A Friendly Ghost

In 2005, Claude Duvall featured in the Travel Channel’s Haunted Hotels documentary series in an investigation into the existence of his ghost. Apparently, Claude is still very much with us in spirit as he reputedly haunts ‘The Marquis’ pub (formerly Hole in the Wall) on Chandos Street in London, as well as the Holt Hotel on the A4260 in Oxfordshire, where he is known to have spent many nights during his highwayman career. Very much in character, he has a reputation of being a very friendly ghost.

Radio

In 2006, Duvall was the subject of an episode of the podcast radio-play, Adventures of Sage & Savant. In May 2015, he was also the subject of the London Dungeon exhibition.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, you can find other features on notorious highwaymen by clicking on https://www.fiveminutesspare.com/education/category/people/highwaymen/

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 61102 additional Info to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 81570 more Information on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 80755 more Info on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 86625 more Info to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 87001 additional Information to that Topic: fiveminutesspare.com/education/highwaymen-claude-duvall/ […]